According to the Placenames Database of Ireland, there are 3 places called Drumcliff in Ireland. Two of these are former monastic settlements and have a round tower to take a look at. The third one in Donegal needs to up its game, though I’m sure it’s very nice too. I haven’t been to the most famous of the Drumcliffs since I was a kid – this is the one where WB Yeats’s grave is to be found (note I didn’t say bones…). Instead, I’ll talk about the lesser known (but by no means inferior) Drumcliff in Co. Clare.

There isn’t a lot known about the monastic settlement which once stood here. It is believed to have been founded by St. Conal/Conald, possibly in the 7th century. There are no records of the monastery in any of the annals which document such things. Still, there’s a round tower here and that’s what I came for 🙂

Drumcliffe is about 4km from Ennis and it’s obvious that there have been a lot of people buried in the area over a considerable period of time. There are two cemeteries on either side of the road and a reasonably large car park. As you might have guessed, the round tower is to be found in the older of the two cemeteries.

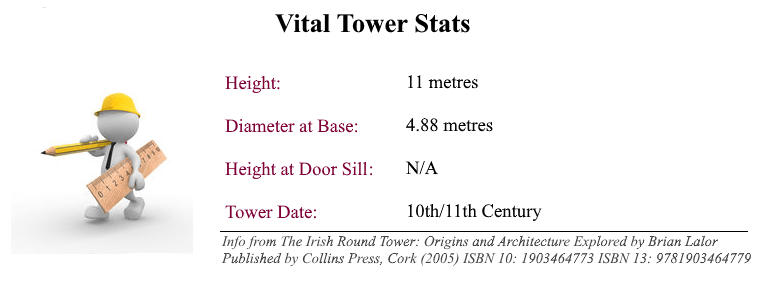

The old cemetery is dedicated to St. Senan and is on a hill which slopes up from the road. The tower is on the right hand side of the cemetery, towards the top of the hill. It stands beside a ruined 15th church which is believed to have replaced the original one for which the tower would have been a belfry. Sadly, the tower is also in ruins and stands just 11 metres in height. Still, if you’re interested in how these towers were built this one will give you an idea. You can see how thick the walls were and how they were constructed.It’s also possible to see where the internal floors would have been. At its lowest, the tower is around 3 metres from the ground.

The cemetery itself is a lovely place to wander around. There are lots of interesting old graves, including many from people who obviously had plenty of money. That contrasts with other parts of the cemetery where there are mass graves. The pauper’s grave was used up until the 1950s. Many of the vicims of a cholera outbreak in the 1830s were buried here, close to a slightly later mass grave for those who perished in the Great Famine of the 1840s. It is thought that are there are around 350 cholera victims buried in the cholera plot and about 2,000 in the famine plot. They were grim times indeed.

Given how hilly and uneven this cemetery is, keeping the grass cut must be quite a challenge. Still, the cemetery is well maintained and makes it a pleasant place to visit.

Getting There

This one is nice and easy to find. Close to Ennis, there is no shortage of car parking. Then it’s just a matter of walking through the cemetery gates and climbing the hill. The tower isn’t easily seen from the road but it’s easy to find.

Date of Visit: 17th September 2020

Height: 21.5m

Height: 21.5m